Inside the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression, 1931-1940

Hooverville was a popular name for shanties spread across the United States during the Great Depression. He was named after Herbert Hoover, who was the President of the United States during the onset of the Depression and was widely blamed for it.

Americans affixed the president's name to these shackles because they were dismayed and frustrated by Hoover's inability to effectively deal with the growing economic crisis. Shocked and confused by the crisis, he held Hoover personally responsible for the state of the economy.

Most large cities built municipal housing houses for the homeless, but the recession caused a rapid increase in demand. The homeless clustered in shack towns near free soup kitchens. These settlements often encroached upon private land, but were often tolerated or neglected because of necessity.

Some of the people who were built to live in these conditions had construction skills and were able to build their houses out of stone. However, most people resorted to building their homes out of boxwood, cardboard, and any scrap of metal. Some even lived in water bodies or slept on the ground. Most were forced to beg for food from those lucky enough to get housing during this era.

Several other terms came into use during this era, such as "Hoover blanket" (an old newspaper used as blanketing) and "Hoover flag" (an empty pocket protruding from the inside).

"Hoover leather" was the cardboard used to line a shoe with the shoe wearing the sole. A "Hoover wagon" was a car tied to horses because the owner could not afford gasoline.

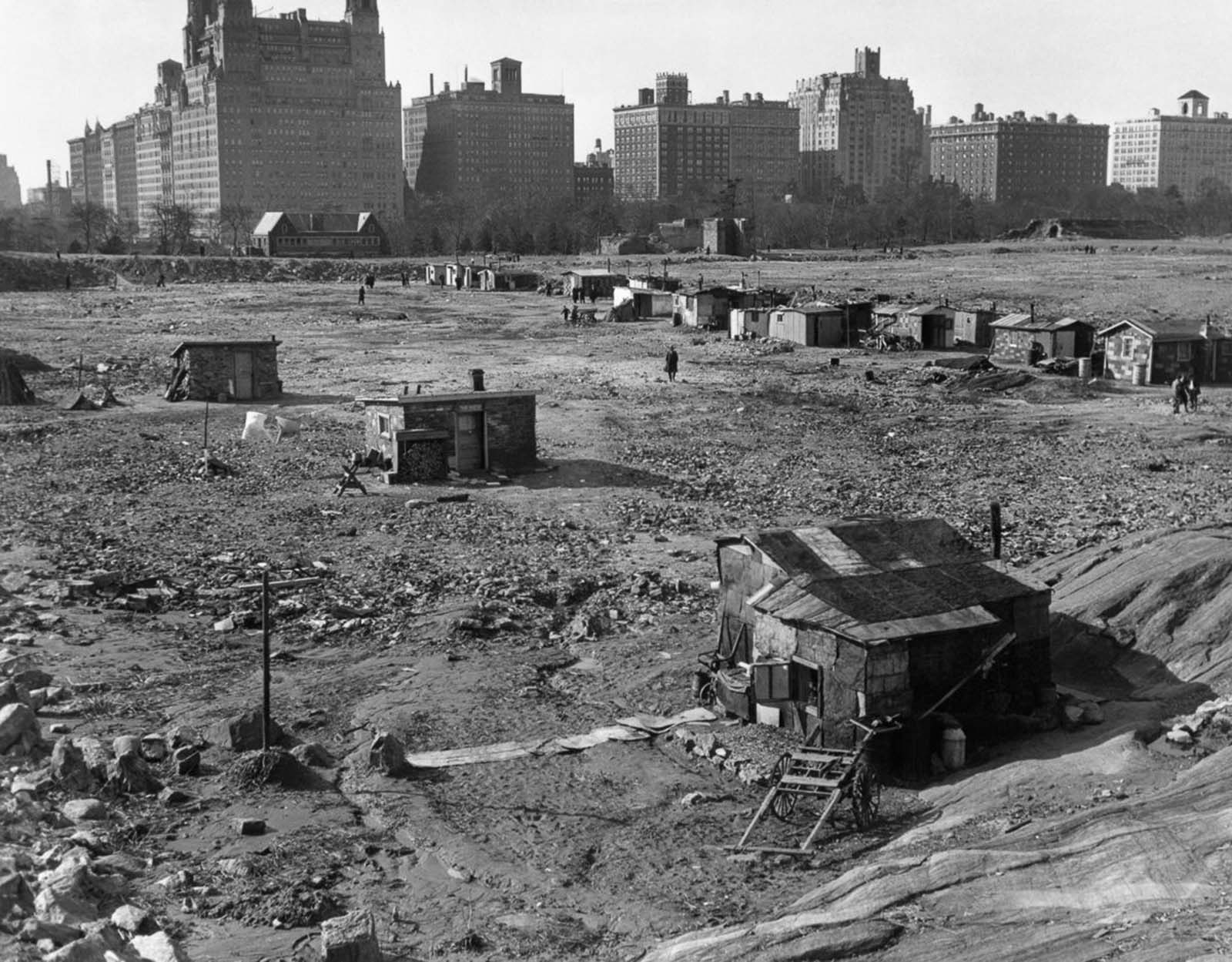

One of the most famous Hoovervilles was located in New York City on what is now the Great Lawn of Central Park. When the stock market crashed in 1929, it happened just as a rectangular reservoir north of Belvedere Castle was being taken out of service. By 1930, some homeless people set up an informal camp in the dry reservoir, but were soon evicted.

But, with nowhere to go, they withdrew and as the New Yorkers' sentiment became more sympathetic, they were allowed to stay. Called "Hoover Valley", the reservoir soon sported a number of shacks labeled "Depression Street". One was even made of brick, the roof of which was made by unemployed bricklayers.

Others built a dwelling out of stone blocks of the reservoir, including a hut that was 20 feet tall. While the settlement may not have been popular among the tenants of the new Fifth Avenue and Central Park West apartments, they did not object.

There were other such settlements in New York - called "Hardluxville", with about 80 huts on the East River between Ninth and 10th Streets.

Another was present with Hudson in Riverside Park called "Camp Thomas Paine". Central Park disappeared shortly before April 1933 when work on the reservoir's landfill resumed.

In Seattle, Washington was home to one of the largest, longest-standing and best-documented Hoovervilles in the country, standing for ten years between 1931 and 1941.

Chicago, Illinois grew at the foot of Randolph Street near Hooverville Grant Park, which also claimed its own form of government, with a man named Mike Donovan, a disabled former railroad brakeman and miner, as the "mayor".

In an interview with a reporter, Donovan would say "building may have stalled elsewhere, but everything is booming here.

We have a kind of communist government. We pool our interests and when the commissionerate shows signs of shortage, we appoint a committee to see what is left in the hotels. ,

After 1940 the economy recovered, unemployment fell, and shack housing abolition programs destroyed all Hoovervilles.

No comments: