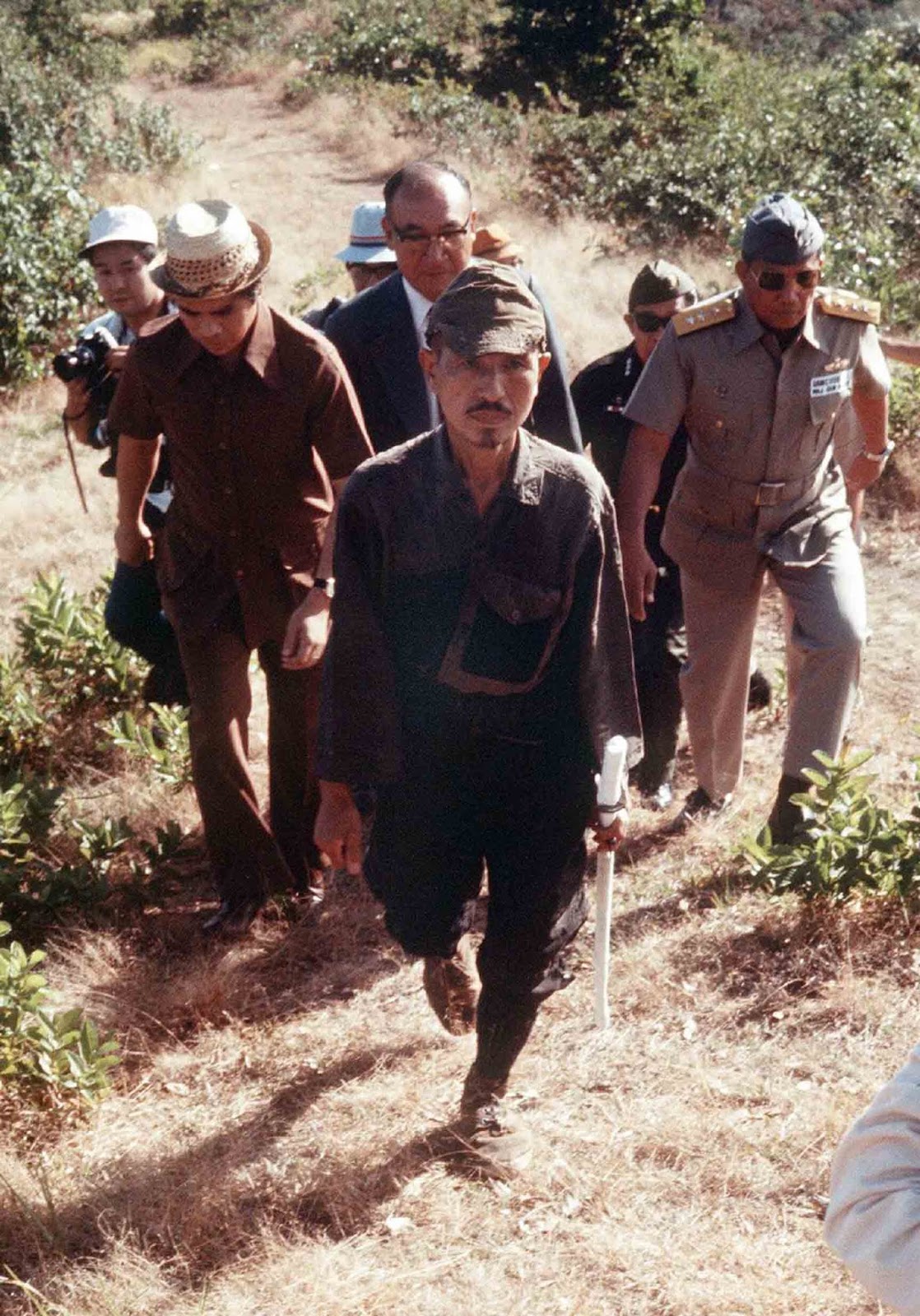

Hiroo Onoda, the soldier who refused to surrender, 1974

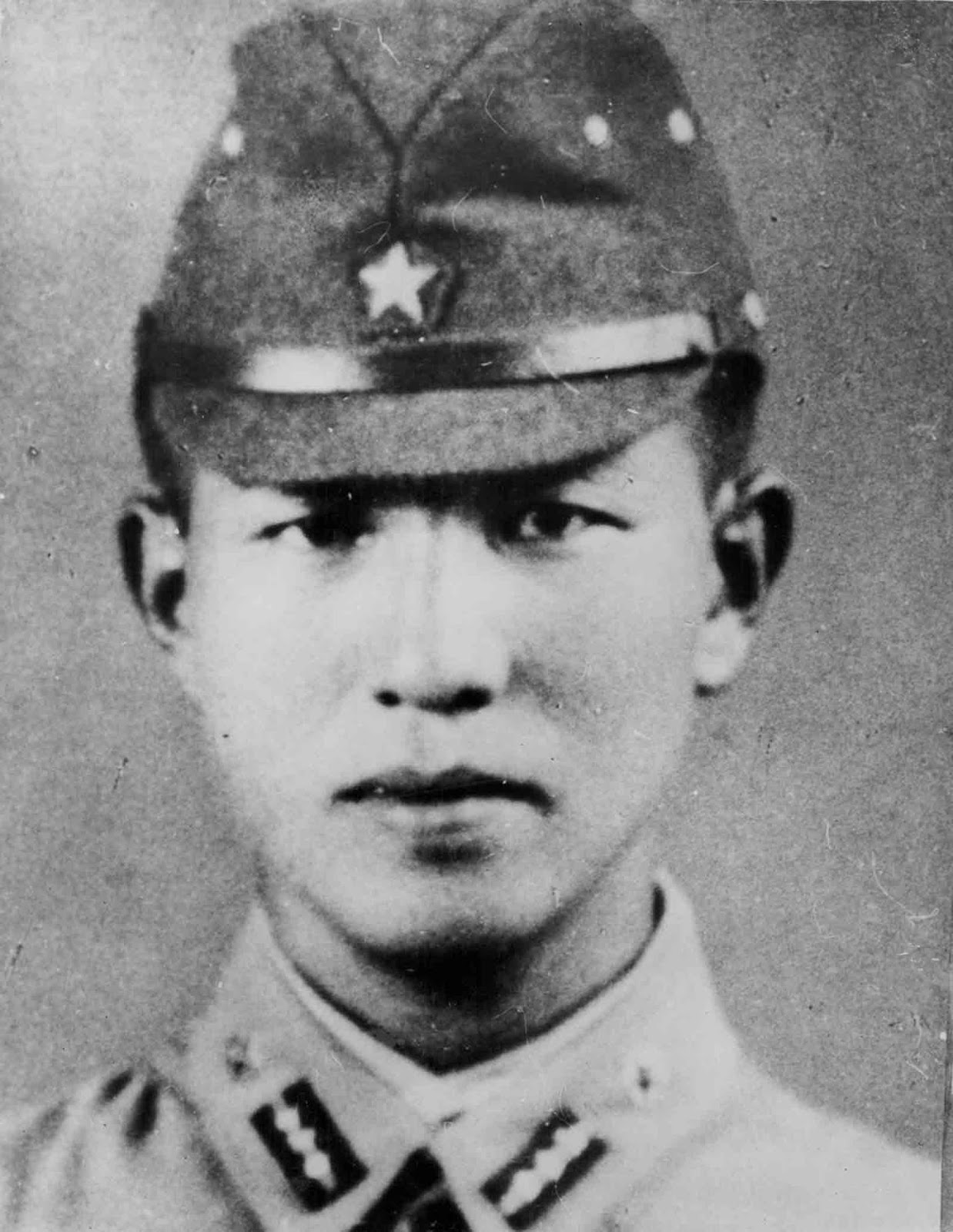

Lieutenant Hiro Onoda is most famous of the so-called Japanese holdouts, a collection of Imperial Army strugglers who hid in the South Pacific for many years after World War II ended.

An intelligence officer, Onoda had been on Lubang since 1944, a few months before the Americans invaded and recaptured the Philippines. Final instructions received from his immediate superior ordered him to retreat into the interior of the island - which was small and in truth of least importance - and harass the Allied occupying forces until the Imperial Japanese Army. Doesn't come back eventually.

"You are absolutely forbidden to die with your own hands", he was told. "It may take three years, it may take five years, but whatever happens, we will come back for you. Till then, as long as you have a soldier, you have to keep leading it."

Onoda continued his campaign as a Japanese holdout, initially living in the mountains with three fellow soldiers (Private Yuichi Akatsu, Corporal Shuichi Shimada and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka). During their stay, Onoda and his accomplices carried out guerrilla activities and engaged in several gunfights with the police.

For the first time he saw a leaflet declaring the surrender of Japan in October 1945; Another cell had killed a cow and found a leaflet left by the islanders that read: "The war ended on August 15. Come down from the mountain!".

However, he distrusted the leaflet. He concluded that the leaflets were Allied propaganda, and also believed that if the war had indeed ended, they would not have been shot.

In late 1945, leaflets with a surrender order printed on them were dropped from the air from General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Fourteenth Field Army.

They were in hiding for over a year, and this leaflet was the only evidence they had that the war was over. Onoda's group looked at the leaflet very closely to determine if it was real and decided it was not.

One of the four, Yuichi Akatsu, walked away from the others in September 1949 and surrendered to the Filipino army six months later in 1950. It seemed like a security issue to others and they became even more careful.

Letters and family photographs were dropped from the plane in 1952 urging them to surrender, but the three soldiers concluded it was a ploy.

In June 1953, during a shootout with local fishermen, Shimada was shot in the leg, after which Onoda brought him back to recovery. On May 7, 1954, Shimada was shot and killed by a search party looking for men.

Kozuka was killed by two bullets fired by local police on October 19, 1972, when he and Onoda, as part of their guerrilla activities, were burning rice collected by farmers. Onoda was now alone.

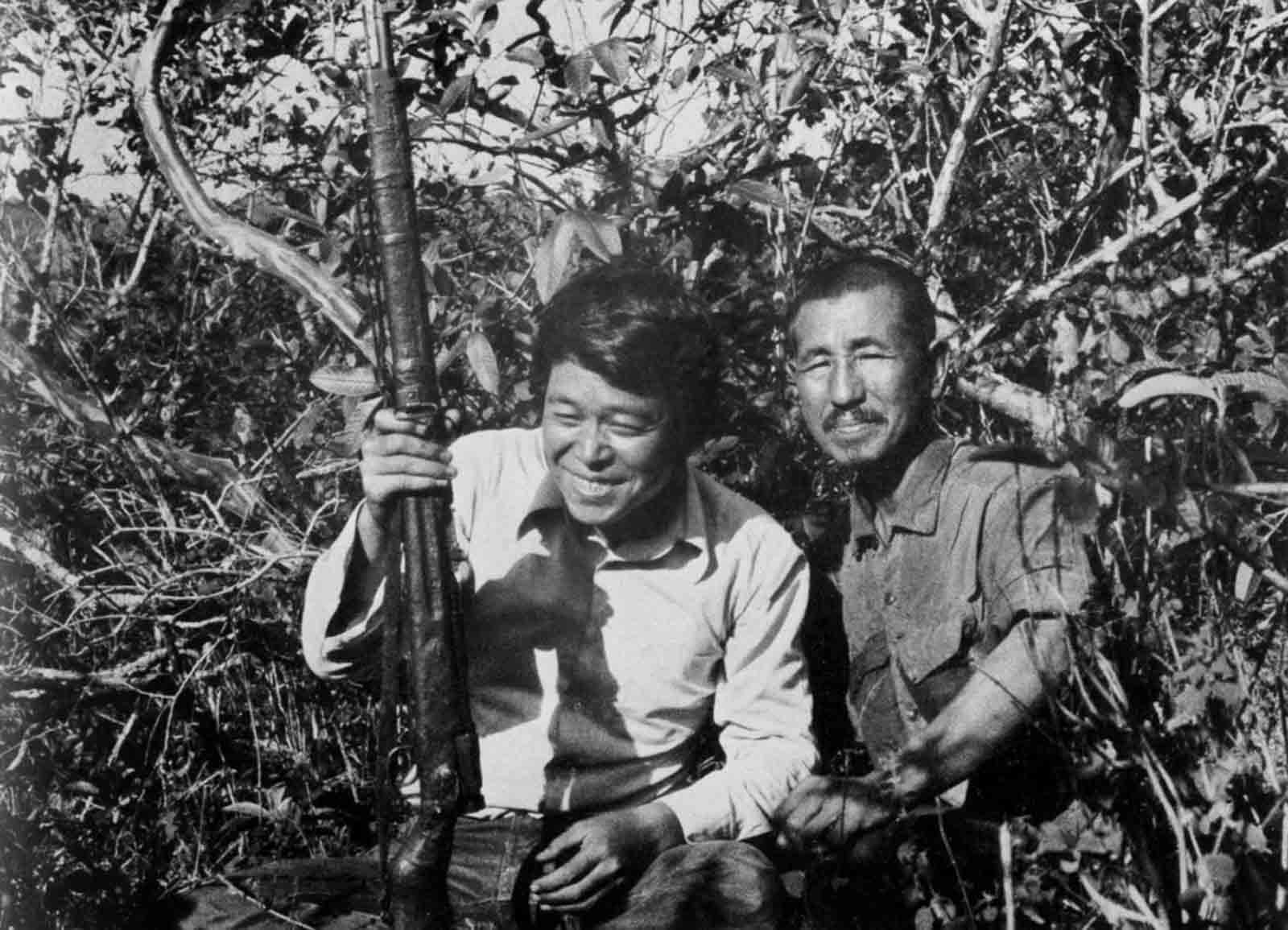

On February 20, 1974, Onoda met a Japanese man, Norio Suzuki, who was traveling around the world looking for "Lieutenant Onoda, a panda, and abominable snowman in that order".

After four days of searching, Suzuki found Onoda. Onoda described the moment in a 2010 interview: "This hippie boy Suzuki came to the island to hear the feelings of a Japanese soldier. Suzuki asked me why I wouldn't come out...". Onoda and Suzuki became friends. But Onoda still refused to surrender, saying that he was waiting for orders from a superior officer.

Suzuki returned to Japan with photographs of himself and Onoda as evidence of their encounter, and the Japanese government found Onoda's commanding officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, who had since become a bookseller. He flew to Lubang, where, on March 9, 1974, he finally met Onoda and fulfilled the promise made in 1944, "Whatever happens, we will be back for you," by issuing him the following command:

- According to the Imperial Command, the Fourteenth Field Army has ceased all combat activities.

- As per Military Headquarters Command No. A-2003, Staff Headquarters Special Squadron is relieved of all military duties.

- Units and individuals under the command of a Special Squadron should immediately cease military activities and operations and place themselves under the command of the nearest superior officer. When an officer cannot be found, they must communicate with American or Philippine forces and follow their instructions.

Onoda was thus appropriately relieved of duty, and surrendered. He carried his sword, his working Arisca Type 99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition, and several grenades, as well as several grenades his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself if he was caught.

Although he had killed people and was involved in a shootout with the police, the circumstances (namely, he believed the war was still going on) were taken into account, and Onoda received a pardon from President Ferdinand Marcos. .

After returning to Japan, Onoda was so popular that some Japanese urged him to run for DIET (Japan's bicameral legislature). He released a ghost-written autobiography, No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War, shortly after his return, detailing his life as a guerrilla fighter in a war that had long been over. .

He was reportedly unhappy at being the subject of so much attention and was troubled by what he saw as the disappearance of traditional Japanese values.

In April 1975, he followed the example of his older brother Tadao and left Japan and moved to Brazil, where he raised cattle. They married in 1976 and played a major role in Colonia Jamic (Jamiq Colony), a Japanese community in Mato Grosso do Sul, Terrenos, Brazil.

No comments: