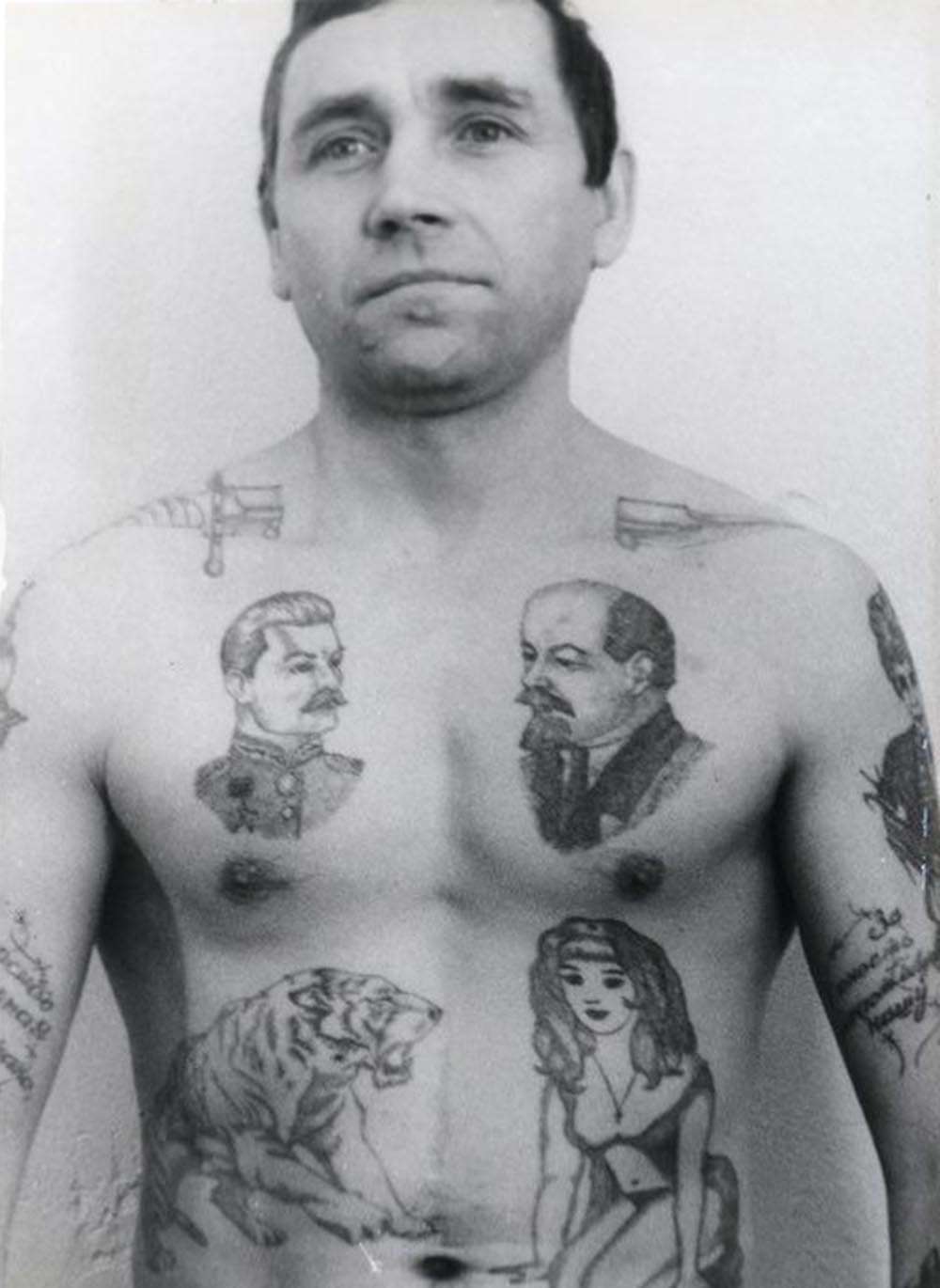

Rare photographs from coded world of Russian criminal tattoos, 1960-1990

In prisons and prisons around the world, tattoos can become an important part of a prisoner's uniform, marking not only the crime they are for but also serving as a way to communicate with others.

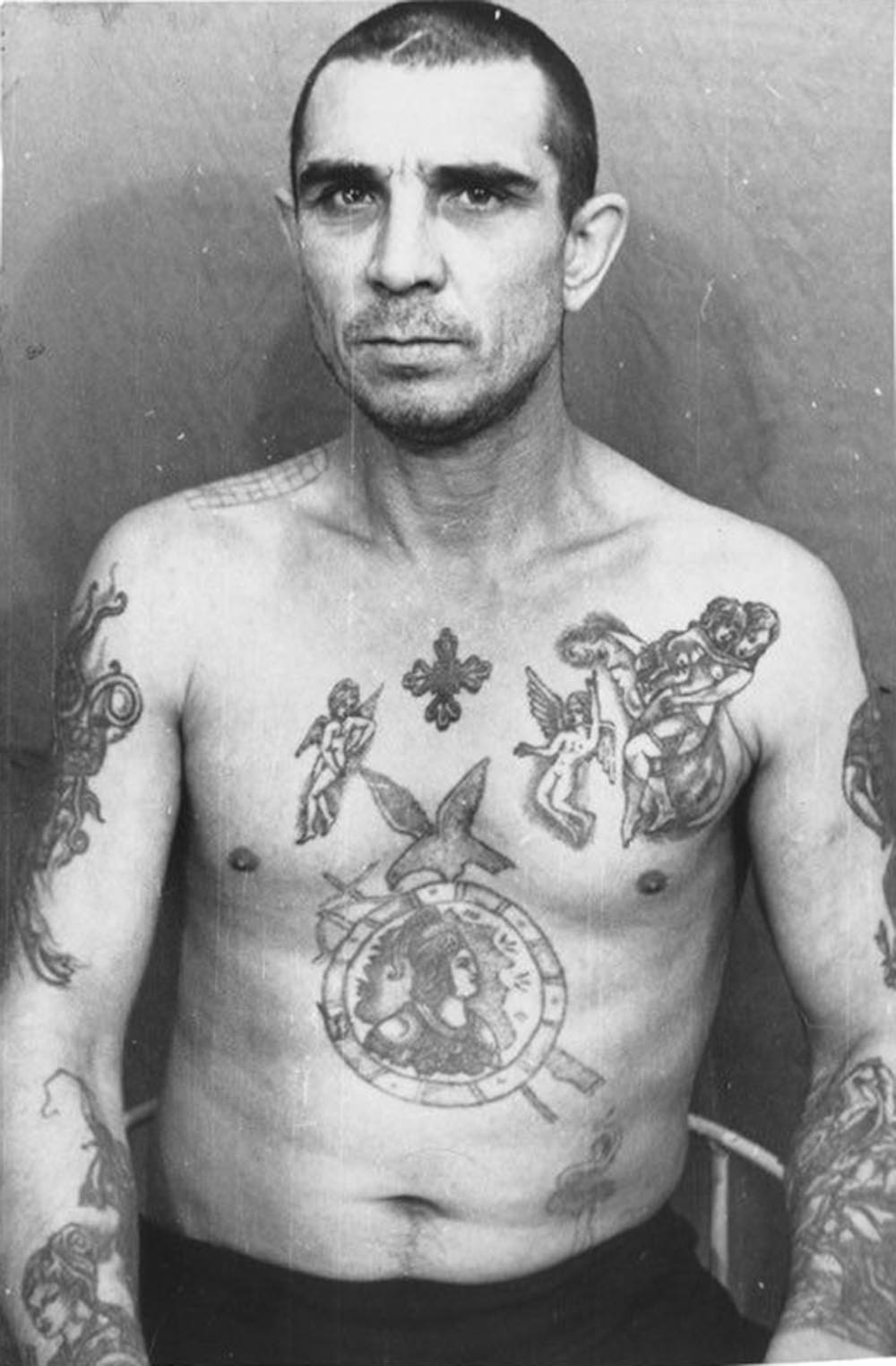

Arkady Bronnikov, considered Russia's leading expert on tattoo iconography, recently released a collection of nearly 180 photographs of criminals lodged in Soviet penal institutions. The Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files, published by FUEL, is possibly the largest collection of prison tattoo photos at 256 pages.

In the 1930s, Russian criminal castes began to emerge, such as masti (suits) and vor v zakon (Rus. ор в аконе) or blatny (official thieves), and with it a tattoo culture to define rank and prestige. Until World War II, any tattoo could denote a professional criminal, with the only exception being tattoos on sailors.

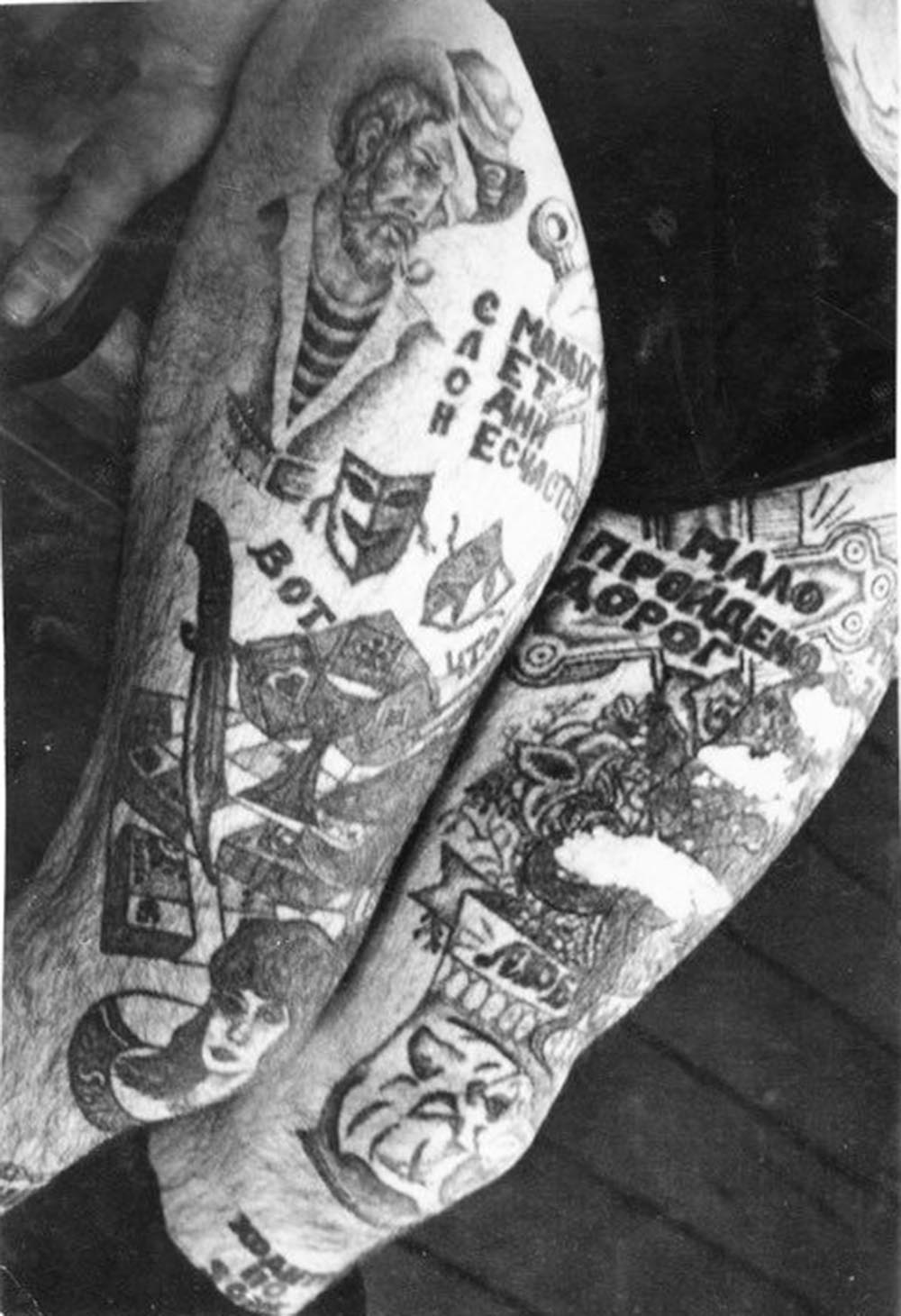

A thief's collection of tattoos represents his "suit" (mast), his position within the thieves' community and his control over other thieves within the thieves' law. In Russian criminal jargon or fenya (феня), a complete set of tattoos is known as a frak es ordenami (a tailcoat with decorations).

Tattoos show a "service record" of achievements and failures, prison sentences, and the type of work a criminal did. They may also represent their "thief's family", naming others with a heart within or a traditional tomcat image.

Misuse of a "lawful thief" tattoo could be punished with death, or the prisoner would be forced to amputate himself with "a knife, sandpaper, a piece of glass or a lump of brick".

In the 1950s Nikita Khrushchev announced a policy for the abolition of criminality from Soviet society. Along with propaganda condemning the "traditional thief" grew in popularity in Russian culture, punishment in prisons intensified for anyone identified as a legitimate thief, including beatings and torture. .

As a response to this persecution, thieves' laws were intensified and punishments for prisoners wearing unearned tattoos ranged from removal to rape and murder.

By the 1970s, the intensification of thieves' laws had resulted in retaliation against lawful burglars, conducted by prison officers who often threw a lawful thief into cells with the prisoners they had punished or was raped. To ease tensions, criminal leaders outlawed rites of passage and outlawed rape as a punishment.

Fights between prisoners were outlawed and conflicts were to be resolved through mediation by senior thieves. Additionally, a fashion for tattooing had spread in juvenile prisons, leading to an increase in the number of inmates with "illegitimate" tattoos.

This ubiquity, coupled with a reduction in violence, meant that "criminal authorities" stopped punishing "unearned" tattoos.

In 1985, new growth in perestroika and tattoo parlors made tattoos fashionable, diluting the status of tattoos as an outright criminal attribute.

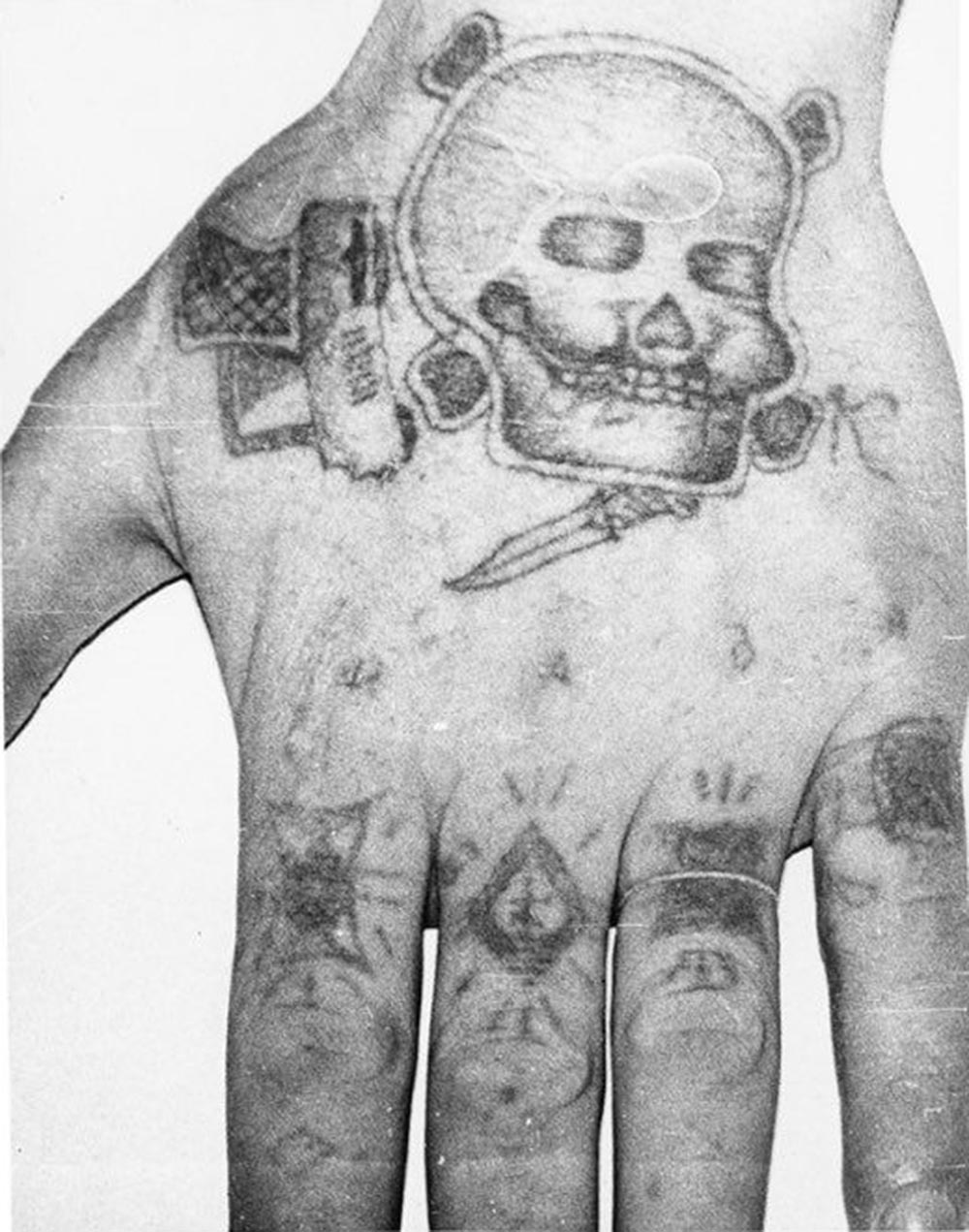

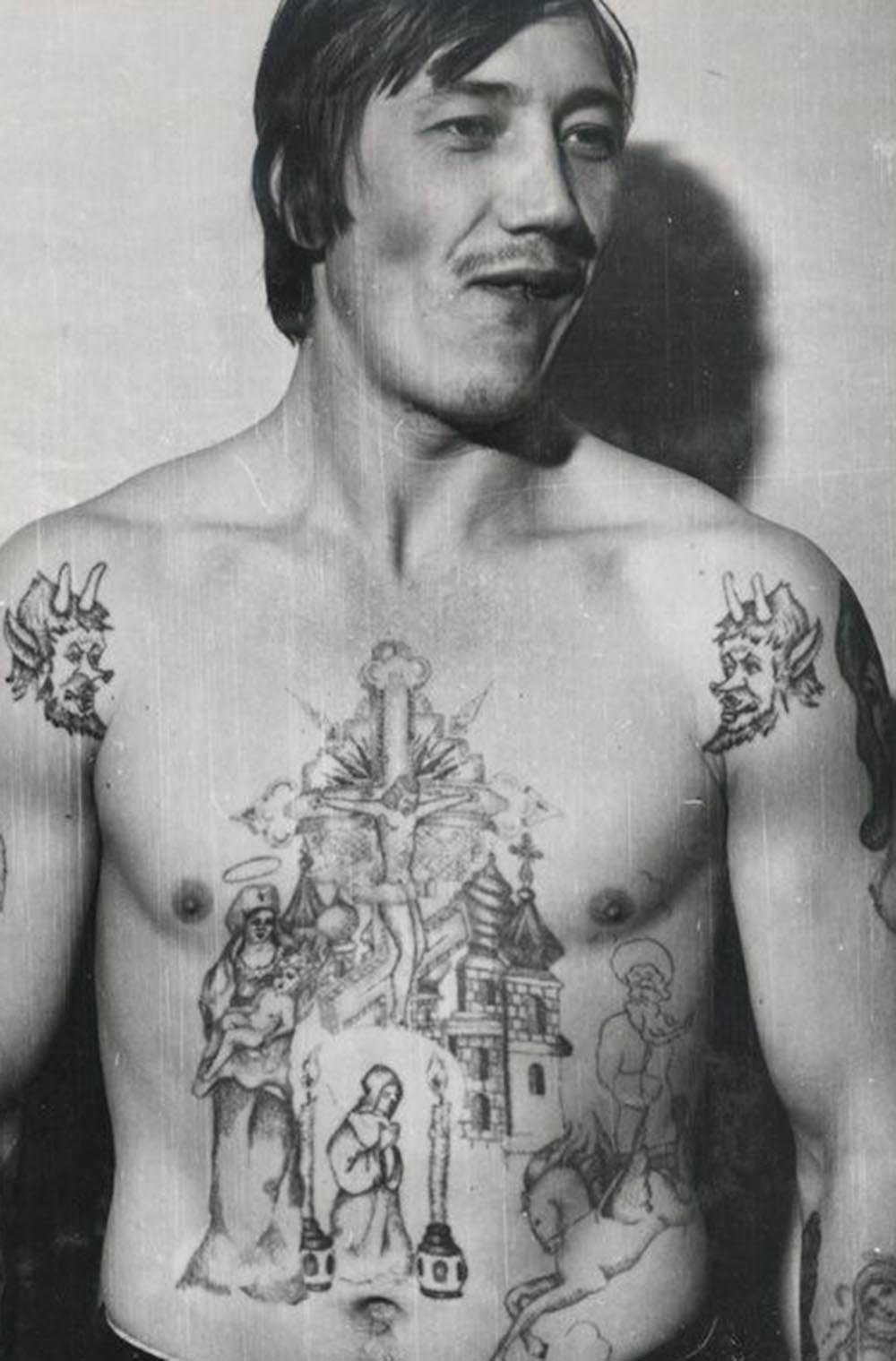

Common designs and themes evolved over the years, often having different meanings depending on the location of the tattoo. Imagery often doesn't literally mean what it is portraying – for example, tattoos displaying Nazi imagery represent a rejection of authority rather than an adherence to Nazism.

Combinations of imagery, such as roses, barbed wire and daggers, create combined meaning. According to lexicographer Alexei Plutser-Sarno, tattoos become "the real aspects of their lives". They symbolize the owner's commitment to the war against the non-thieves, the police (psychic), and the "bitch" (suka).

The environment in the Soviet era was one of heavy visual propaganda, and tattoos are a response to that, and a "grin on the right" (oskal na vlast), often directly parodying official Soviet slogans with Communist Party leaders often referred to as devils. is depicted as, donkey, or boar.

No comments: