Striking photographs capture the daily life of African Americans in Chicago's South Side, 1941

From 1910 to 1960 the Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African-Americans from the South to Chicago, where they became an urban population. They created churches, community organizations, businesses, music and literature.

African Americans of all classes formed a community on the South Side of Chicago for decades along with the Civil Rights Movement on the West Side of Chicago.

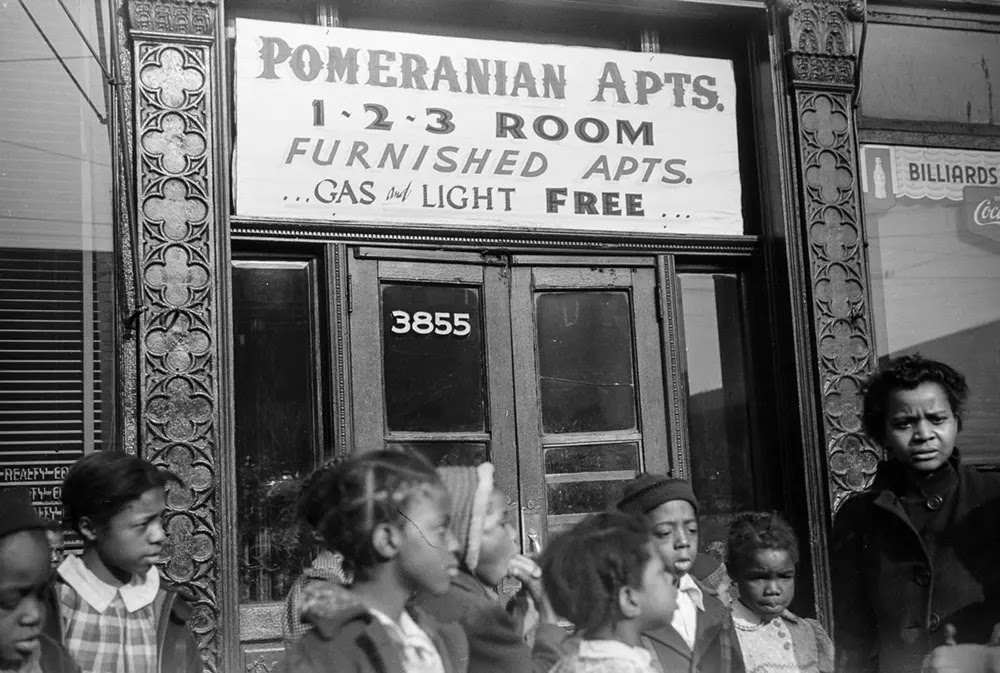

In the spring of 1941, Farm Security Administration photographer Edwin Roskam toured the Black Belt, roaming the streets and photographing generations of black Chicagoans.

Living in separate communities, almost regardless of income, Chicago's black residents aimed to create communities where they could survive, sustain themselves, and set their own course in Chicago history. get the ability to.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, Chicago's South Side was a center of African-American culture and trade. The neighborhood known as "Bronzeville" was surprisingly small, but at its peak, more than 300,000 lived in the narrow, seven-mile strip.

Chicago's black population extends from 22nd to 63rd Streets between State Street and Cottage Grove. But Bronzeville's pulsating energy lay at the congested corners of 35th and State Streets and 47th Street and South Parkway Boulevard (later renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive).

At those intersections, people flocked to see and be seen, shop, do business, dine and dance, and experience this bustling black metropolis.

The crowd reflected a diverse mix of people living in the Black Belt: young and old, poor and rich, professionals and laborers.

Bronzeville was famous for its nightclubs and dance halls. Jazz, blues and gospel music developed with the migration of Southern musicians, attracting a diverse audience and fans.

Chicago's black population developed a class structure, consisting of large numbers of domestic workers and other manual laborers, along with a small, but growing, contingent of middle- and upper-class business and professional elites.

In 1929, black Chicagoans gained access to city jobs and expanded their professional class. Fighting job discrimination for African Americans in Chicago was an ongoing battle, as foremen in various companies restricted the advancement of black workers, often preventing them from earning higher wages. In the middle of the 20th century, blacks gradually began to move to better positions in the workforce.

No comments: