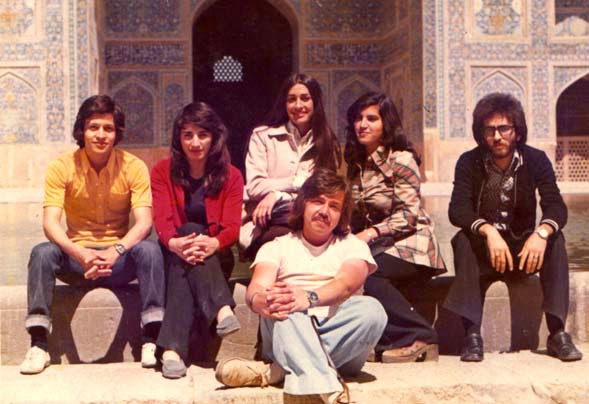

Vintage photos capture everyday life in Iran before the Islamic Revolution, 1960s-1970s

The Islamic Republic imposes strict rules on Iranian life. This extended photo collection shows Iranian society before the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and, it is clear, that Iran was a very different world.

It was also a world that looked brighter for women. And, as everyone knows, when things get better for women, things get better for everyone. After the revolution, 70 years of progress in Iranian women's rights were withdrawn almost overnight.

The 1979 revolution, which brought together Iranians from many different social groups, has its roots in Iran's long history.

These groups, which included clergy, landowners, intellectuals and businessmen, first came together in the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–11.

However, amidst social tensions, as well as foreign intervention from Russia, the United Kingdom, and later, the United States, efforts at satisfactory reform were continually suppressed.

The United Kingdom helped Reza Shah Pahlavi establish a monarchy in 1921. Along with Russia, the UK pushed Reza Shah into exile in 1941, and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, took the throne.

In 1953, amid a power struggle between Mohammad Reza Shah and Prime Minister Mohamed Mossaddeg, the U.S. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the UK Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) staged a coup against Mossaddeg's government.

Years later, Mohammad Reza Shah dismissed parliament and launched the White Revolution – an aggressive modernization program that increased the wealth and influence of landlords and clerics, disrupted rural economies, led to rapid urbanization and westernization, and democratized democracy. and prompted concerns over human rights.

The program was financially successful, but benefits were not evenly distributed, although the transformative effects on social norms and institutions were widely felt.

Opposition to the Shah's policies was emphasized in the 1970s, when world monetary instability and fluctuations in Western oil consumption seriously threatened the country's economy, with yet high-cost projects and programmes. was directed in large part towards

A decade of extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending and a boom in oil prices led to high rates of inflation and stagnation of Iranians' purchasing power and standard of living.

In addition to increasing economic difficulties, the 1970s led to an increase in socio-political repression by the Shah's regime. Outlets for political participation were minimal, and opposition parties such as the National Front (a loose coalition of nationalists, clerics and non-communist leftist parties) and the pro-Soviet Tadeh ("people's") party were marginalized or outlawed. .

Social and political protests were often met with censorship, surveillance, or persecution, and illegal detention and torture were common.

For the first time in more than half a century, secular intellectuals—many of whom were fascinated by the populist appeal of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a former professor of philosophy at Qom, who was exiled in 1964 after speaking harshly against the Shah's recent was. The reform program- abandoned its objective of reducing the authority and power of Shia ulama (religious scholars) and argued that, with the help of the ulama, the Shah could be overthrown.

In this atmosphere, members of the National Front, the Tadeh Party and their various different groups now joined the Ulama in widespread opposition to Shah's rule.

Khomeini continued to preach about the evils of Pahlavi rule in exile, accusing the Shah of wrongdoing and subjugation to foreign powers.

Thousands of tapes and print copies of Khomeini's speeches were smuggled back into Iran during the 1970s, as a growing number of unemployed and working-poor Iranians—mostly new migrants from rural areas—disillusioned with the cultural void of modern urban Iran. Had become - Ulema for guidance.

The Shah's reliance on the United States, his close ties with Israel—then engaged in extended hostilities with heavily Muslim Arab states—and his regime's non-negotiable economic policies fueled the power of dissenting rhetoric with the public.

Externally, everything was going well in Iran, with a rapidly growing economy and rapidly modernizing infrastructure.

But in just a little over a generation, Iran had transformed from a traditional, conservative and rural society to an industrial, modern and urban one.

The feeling that too much effort was put into both agriculture and industry too soon and that the government, either through corruption or inefficiency, failed to deliver what it was promised, manifested in the 1978 anti-government demonstrations was.

Demonstrations began in October 1977, amid widespread tensions between Khomeini and the Shah, which developed into a campaign of civil resistance, which included both secular and religious elements.

Protests rapidly intensified in 1978 as a result of the burning of the Rex cinema, which was seen as the trigger for the revolution, and between August and December of that year, strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country.

On 16 January 1979, the Shah left Iran and went into exile as the last Persian emperor, leaving his duties as a regency council and Shapor Bakhtiyar, an opposition-based prime minister.

Ayatollah Khomeini was invited back to Iran by the government, and returned to Tehran to be greeted by several thousand Iranians.

The imperial rule collapsed on 11 February, when guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed soldiers loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting, bringing Khomeini to official power.

The Iranian people voted in a national referendum on 1 April 1979 to become an Islamic republic and to create and ratify a new democratic-republic constitution, making Khomeini the country's supreme leader in December 1979.

No comments: