Laika: The Soviet Space Dog Sent on a One-Way Trip into Orbit, 1957

In the early days of the Space Race, the Soviet Union sought to establish its dominance in space exploration. One of the most important milestones in this quest was the launch of Sputnik 2, aboard the first living creature to orbit Earth: a dog named Laika.

The achievement was hailed as a victory for Soviet engineering and innovation, but it came at a heavy price. Laika's mission was a one-way trip, and she went into space just hours after launch.

The experiment, which monitored Laika's vital signs, was intended to prove that a living organism could survive being launched into orbit and continue to function in conditions of weaker gravity and increased radiation, allowing scientists to travel to space. The first data on the biological effects of the vehicle could be obtained.

Despite her short life, Laika became a symbol of bravery and sacrifice, capturing the imagination of people around the world and inspiring future generations of space explorers.

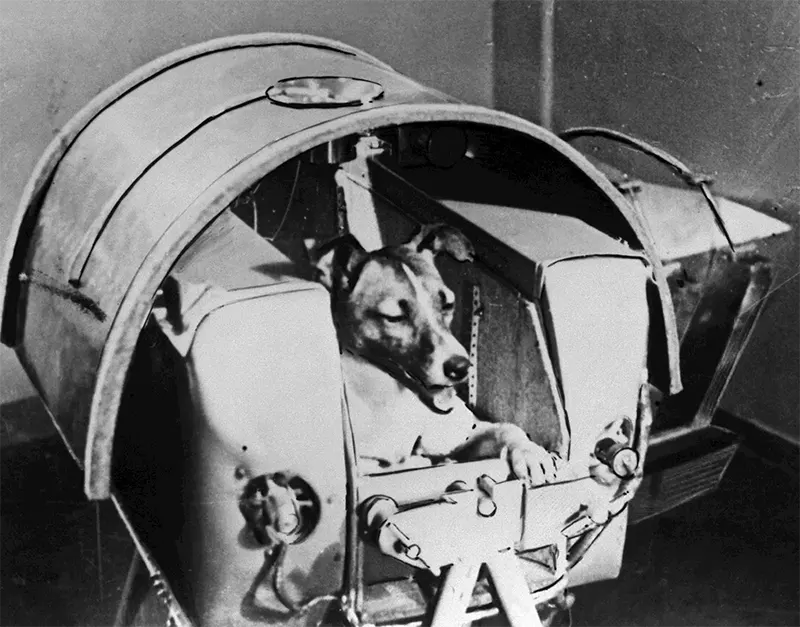

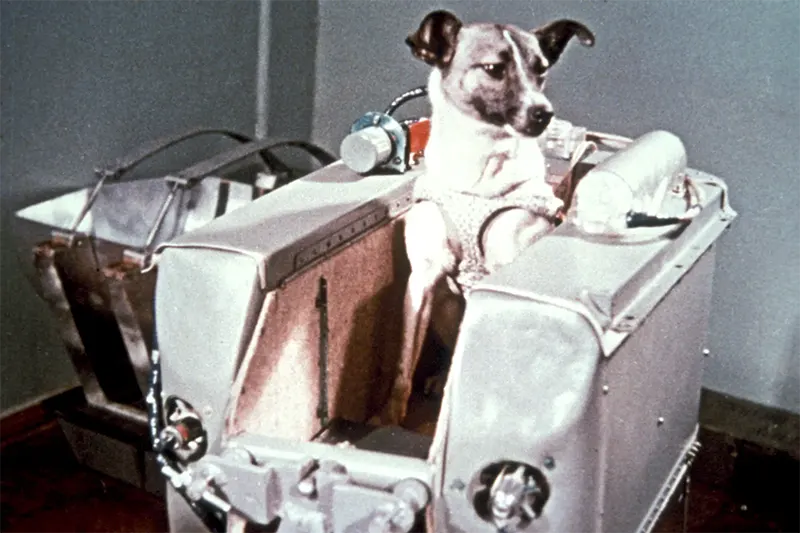

A week before the launch Laika was found wandering the streets of Moscow. Soviet scientists chose to use the Moscow stray because they assumed that such animals had already learned to tolerate conditions of extreme cold and hunger. She was a 5 kg (11 lb) hybrid female, approximately three years old.

Soviet personnel gave him several names and nicknames, among them Kudryavka (Russian for Little Curly), Zhukka (Little Bug) and Limonchik (Little Lemon).

Laika, the Russian name for several breeds of dogs similar to the Husky, was the popular name around the world. Its literal translation would be "barker".

The American press dubbed him Mattnick (mutt + suffix -nick), as a pun on Sputnik, or referred to him as Curly. Her true lineage is unknown, although it is generally accepted that she was part Husky or another Nordic breed, and possibly part Terrier.

The Soviet Union and the United States had previously only sent animals on suborbital flights. Three dogs were trained for the Sputnik 2 flight: Albina, Mushka, and Laika. Soviet space-life scientists Vladimir Yazdovsky and Oleg Gazenko trained the dogs.

To acclimatize the dogs to the small cabin of Sputnik 2, they were placed in progressively smaller cages for periods of up to twenty days.

The extensive close confinement made them stop urinating or defecating, made them restless, and worsened their general condition.

Laxatives did not improve their condition, and researchers found that only long-term training proved effective.

The dogs were placed in centrifuges that simulated the acceleration of a rocket launch and placed in machines that simulated the noise of a spacecraft.

Before launch, one of the mission's scientists took Laika home to play with his children. In a book chronicling the story of Soviet space medicine, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky wrote, "Lika was calm and charming ... I wanted to do something good for her: she had little time left to live."

Yazdovsky made the final selection of the dogs and their designated roles. Laika was to be a "flying dog"—a sacrifice for science on a one-way mission to space.

Albina, who had already flown twice on a high-altitude test rocket, was to serve as Laika's backup. The third dog, Mushka, was a "control dog"—he was to remain on the ground and be used to test instrumentation and life support.

Before leaving for the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Yazdovsky and Gazenko performed surgery on the dogs, routing cables from transmitters to sensors that measured breathing, pulse and blood pressure.

According to a NASA document, Laika was placed in the satellite's capsule on October 31, 1957, three days before the start of the mission.

At that time of year, the temperature at the launch site was extremely cold, and a hose connected to a heater was used to keep its container warm.

Two assistants were appointed to keep a constant eye on Laika before the launch. Just before she took off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on 3 November 1957, Laika's fur was sponged in a weak ethanol solution and carefully prepped while iodine was painted over the areas where her physiological functions could be monitored. Sensors will be installed for

One of the technicians preparing the capsule before final liftoff: "After placing Laika in the container and closing the hatch, we kissed her nose and wished her a good journey, knowing she would survive the flight." Won't be able to."

Accounts of the time of launch differ by source, with 05:30:42 or 07:22 Moscow time being given. At peak acceleration, Laika's respiration increased to three to four times the pre-launch rate.

Sensors showed that his heart rate was 103 beats/min before launch and increased to 240 beats/min during the initial acceleration.

After reaching orbit, Sputnik 2's nose cone was successfully released; However, the "Block A" core did not separate as planned, preventing the thermal control system from operating correctly.

Some thermal insulation came loose, causing the cabin temperature to rise to 40 °C (104 °F). After three hours of weightlessness, Laika's pulse rate had stabilized back to 102 beats/min, three times higher than in the earlier ground tests, indicating her stress.

Initial telemetry indicated that Laika was agitated but was consuming her food. After about five to seven hours of flight, there were no signs of life from the spacecraft.

Sputnik 2 was not designed to be recoverable, and it was always accepted that Laika would die. The mission sparked a worldwide debate on animal abuse and animal testing in general to advance science.

In the United Kingdom, the National Canine Defense League called on all dog owners to observe a minute of silence for each day that Laika was in space.

Animal rights groups called on members of the public to protest at the Soviet embassies at the time. Others demonstrated outside the United Nations in New York.

No comments: